And Duvivier’s method of painting the vegetation with solid green areas of enamel overpainted with tiny brown lines to suggest leaves was one that he had used on other porcelain he decorated in England during his first stay (4).(i)

In addition, the airy grey tail feathers of the rooster (1a) recall similar birds he had painted on a Sceaux porcelain water jug, c. 1775, and on a faience plate during his earlier employment at Sceaux, ca. 1766-68, both shown in my book.(ii)

c. 1785-90. Private collection. Photo: Pat Preller

c. 1785-90. Private collection. Photo: Pat Preller

I noticed that two of the tea bowls in the New Hall bird service show feathered subjects closely akin to the specimens on these Hague-decorated Tournai plates. Because the side of a tea bowl (5) offers less space than the center of a plate, the rooster here has to slightly crouch, but his left wing also touches the ground and he has eye contact with another bird at the right. The specimen in the right-hand tea bowl (6), also slightly crouching, is one that Duvivier was clearly repeating with somewhat different coloring after he had depicted it standing in a marshy setting, together with a duck, in the center of the other Tournai plate a few years beforehand (2a).(iii)

But what kind of bird was this with the fluffed up neck feathers? After hunting a bit online, I discovered that it was a male “ruff” (not a heron, as the auction house had surmised). The Google entry states, “The ruff (Philomachus pugnax) is a medium-sized wading bird that breeds in marshes and wet meadows across northern Eurasia. [The smaller female bird is known as a reeve]. It forages in wet grassland and soft mud, probing or searching by sight for edible items. It primarily feeds on insects, especially in the breeding season, but it will consume plant material as well.” In German the name is Kampfläufer, in Dutch Kemphaan, both terms referring to its pugnacious behavior during the breeding season. Different subspecies of the bird have different coloring.

But the origin of the English term ruff for the male bird with its large collar of ornamental feathers is indeed curious. It is said to have been derived from the name for the extravagant lacy collars that were fashionable from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-seventeenth century. One example of such a ruff is shown below in (7).

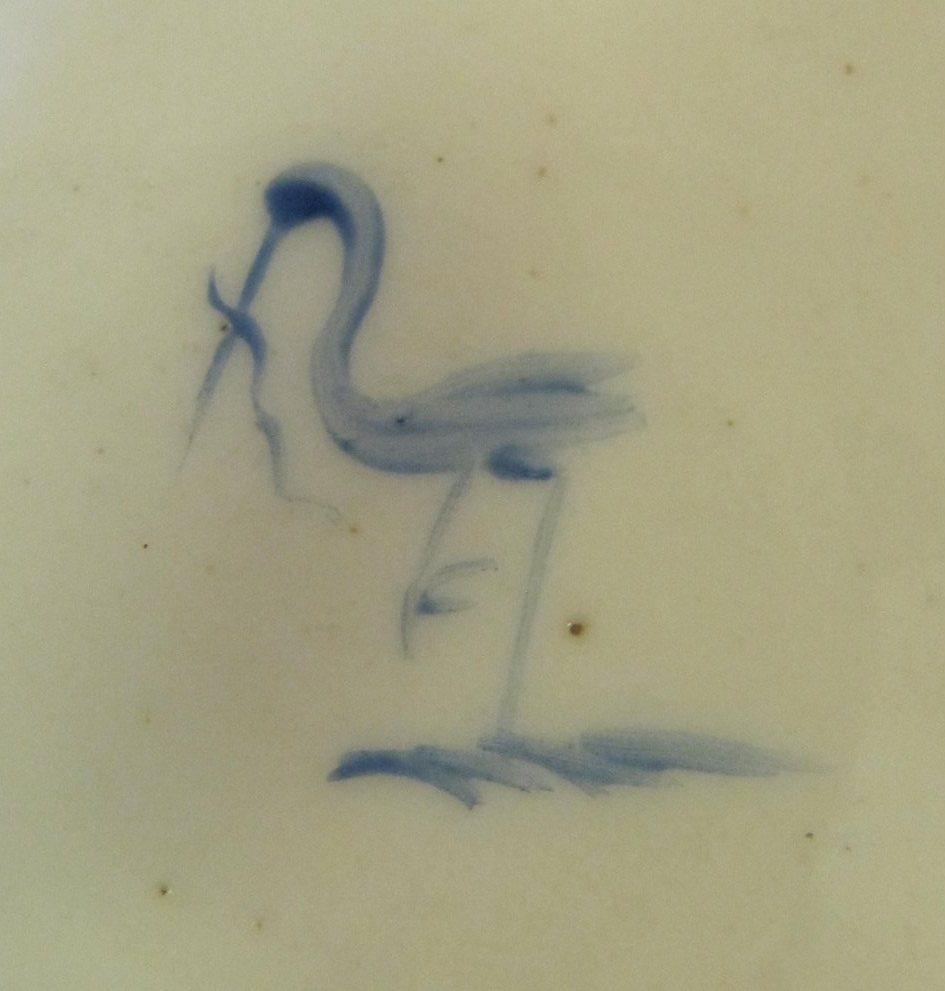

The bird shown in (8) is a stork holding an eel in its bill. It appears (in many variations) on the imported porcelain decorated by the painters of the Lynckers’ decorating business. They imported mainly hard-paste porcelain from Ansbach and soft-paste porcelain from Tournai. In most cases the Tournai pieces were delivered with the cobalt coloring on the rims or elsewhere already added under the glaze (this was a high-firing color and it meant that the painters could add further decoration and gilding, both of which could be fired at lower temperatures). When they founded their business in The Hague in 1775, Anton Lyncker and son chose the stork with the eel as their official mark – borrowed from the city’s coat-of-arms. (For more comments about this business, see In the Footsteps of Fidelle Duvivier, pp. 1, 4, 60, 65, 66, 92-94).

NOTES

(i) See pp. 56, 57 for (62a, b) and (63b), from which detail (4) here is taken.

(ii) See p. 21 for (24) and (23).

(iii) Duvivier painted a ruff again on a milk jug belonging to a second New Hall bird service (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Inv. WA2009.47, Peter Glazebrook bequest). Not published.