In addition to the example shown in my book (Fig. 1), the Sceaux manufactory made bulb pots in a great variety of shapes in faience, and some of those sold at French auctions in recent years were also decorated by Fidelle Duvivier (Figs. 2, 12), as it turns out.(i) What kinds of bulbs bloomed on these delicate devices and what were they filled with? The answers to these questions take us into the history of the cultivated hyacinth in Europe.

Photo: Donald Heald, Rare Books, Prints & Maps, New York, NY

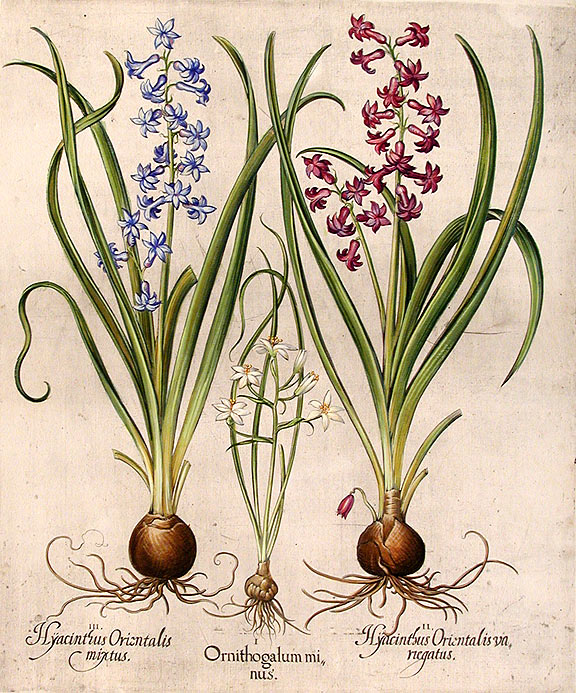

Hyacinthus Orientalis, the common garden hyacinth, originated as a wild flower in Asia Minor, and specimens were first brought to Western Europe during the 16th century. It found its most beneficial new home amongst the “florists” (flower cultivators) of the Dutch city and region surrounding Haarlem, where the sandy, well-draining soil was ideally suited for breeding the plant. There, from the second half of the 17th until the middle of the 18th century, the commercial cultivation of the hyacinth yielded a huge diversity, accomplished by a lengthy process of selection and hybridization. By 1768, according to one French authority, there were over two thousand named varieties being grown in Haarlem.(ii) The bulb-growing Voorhelm family in Haarlem deserves special mention

for contributing to the advancement of this garden treasure. By 1684 Pieter Voorhelm had developed several kinds of double-flowering hyacinths that achieved considerable fame. And in 1752 his grandson George Voorhelm published his Traité sur la Jacinthe (A Treatise on the Hyacinth), which was translated into several languages. Besides containing a sales catalogue listing the finest named bulb varieties offered by his Haarlem firm, it offered valuable planting advice. It is one of several early publications that also illustrate or discuss how to “force” hyacinth bulbs to bloom indoors – and earlier than their normal spring blooming time.(iii) This could be done by either planting the bulb in a pot with soil, or by placing it above water so that the roots would develop in it. The latter method was first done with glass containers of various sizes (cf. Figs. 4, 5, 9) and this seems to have been in practice during the first two decades of the 18th century.(iv)

Fig. 7 Madame de Pompadour (La belle jardinière) by Carle Van Loo, 1754-55.

Palace of Versailles, France (MV8616)

Wikimedia Commons

Besides being a royal mistress, friend, and confidante to Louis XV from 1745 until her death in 1764, the marquise exerted her most profound influence in that period as a patron and supporter of the arts. By 1760 the Manufacture Royale de Porcelaine in nearby Sèvres, heavily subsidized by the royal purse, had received royal commissions to design and create porcelain vases for multiple uses. Some of these undoubtedly came from Madame de Pompadour herself, for despite her frail health, she had a passion for the outdoors and gardening (Fig. 7) – and she was a keen devotee of hyacinths. What is more, she was able to kindle the king’s enthusiasm for all of her horticultural ideas. Every year the king spent on the average of 8000 livres on orders from Haarlem florists for bulbs, and one 1759 bill noted an order for 363 Hyacinth bulbs for beds and 200 “for glasses.”

The elegantly shaped vase shown in Figure 6, which had been introduced in 1756, is listed as a piédestal à oignon in the Sèvres factory records, indicating it was intended to be filled with water so that a bulb (most likely a hyacinth) could be grown on top. These vases were usually grouped in pairs with other shapes to form sets known as garnitures, and placed on mantelpieces and pieces of furniture, often with mirrors behind them to add to the rich decorative effect.(v) Each pedestal-shaped pot was fitted with a separate circular bulb holder with a pierced collar (Fig. 8) that provided stability to grow larger flowers such as hyacinths in water.(vi) When bulbs were out of season, the vases could be used to display cut flowers (or porcelain flowers, also made by Sèvres for customers who could afford them). In light of these multiple uses, these objects are nowadays frequently listed as jardinières (garden/flower pots) or bouquetières in museum inventories and auction literature. La bouquetière is actually defined as a flower container with several cups to accomodate flowers on stems (un vase à plusieurs godets accueillant des fleurs sur tiges) so this would include supporting flowering hyacinths bulbs.(vii) We see some of these built-in “cups” or collars built into the covers of the Sceaux examples here, where they have survived (Figs. 1, 10, 11, 12, 13). The smaller holes in these covers would have held sticks to help support the flowering stalks, if needed.

< Fig. 8 This insert fits at the top of the Sèvres vase piédestal à oignon shown in Fig. 6, and belongs to another such vase porte bulbe in the collection of the Petit Palais, musée des Beaux-arts de la Ville de Paris (OTUCK113-1).

Fig. 9 > Various contemporary glass and ceramic hyacinth vases and containers for the indoor forcing of bulbs with water. Photo courtesy of Julie Berk, U.K. (viii)

Fig. 9 ©Julie Berk

But in the same period there were less costly bulb pots of various shapes being made in French faience, and the Sceaux manufactory created a diverse range of models over the years, as Figure 2 and the following examples illustrate (Figs. 10-13).(ix)

H 16 cm, L 22 cm. Fleur de lys mark in brown. Photo: Pescheteau-Badin, Paris

The rectangular bulb pot in Figure 10 was referred to as a papeterie, and one could imagine it serving as a letter or stationery holder (a kind of desk organizer) when it wasn’t in use for forcing bulbs. Another popular variation on this rectangular model with just one long compartment held a cover with three cups in a row.(x)

It appears that no other faience manufactory made bulb containers in such a wide assortment of shapes as Sceaux did – and this diversity also applies to their decoration. The second period of production under managers Jacques and Jullien (1763-1772) mirrors the transitional tastes of the 1760s and 1770s, when rococo curves were yielding to the straighter geometrical symmetry of the neoclassical style. Interestingly, the pieces shown in Figures 1, 12 and 13 illustrate this transition: the first two examples still display a slight rounded bulge on the upper and lower rims, but like the slightly later bouquetière in Fig. 13, they have molded and painted pilasters. This latter piece is decorated with swags, festoons, and other purely neoclassical elements, and retains the same demi-lune shape. It actually now looks like a piece of furniture, a kind of faience demi-lune commode minus the legs, meant to resemble the tables and commodes of precious woods made during the Louis XVI period.

This demi-lune shape would continue to be used by porcelain manufactories in France (Fig. 14) and it inspired many variations of porcelain and earthenware bulb pots across the Channel in England throughout the first quarter of the 19th century. However, these are usually called “bough pots” now on the assumption that they would have held either bulbs or cut flowers. (xi) Many interesting examples can be found online by using this search term.

H c. 15 cm. ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London (C.12&A-1965)

NOTES

(i) Fig. 2 lot details: “Caisse à fleurs carrée en faïence à décor polychrome de paysages maritimes animés, guirlande de feuillage sur le bord supérieur et entrelacs sur la base. XVIIIe siècle. Hauteur: 13.cm.” Pescheteau-Badin, Paris, auction of 10 June 2015, lot 281.

Fig. 12 lot details: “Bouquetière d’applique en faïence de l’Est à décor en camaïeu de rose de trois paysages animés en réserve. Epoque XVIIIème siècle. H 17.5 cm L 28 cm. … Cortot-Vregille-Bizouard, Dijon, 14 June 2014, lot 188. (Originally attributed to the St. Clément factory).

(ii) Maximilien Henri, Marquis de Saint-Simon, De Jacintes, de leur Anatomie, Reproduction, et Culture (Amsterdam, 1768). An English translation may be found at this link:

http://www.kellscraft.com/DutchBulbs/dutchbulbsapp1.html

(iii) Patricia Coccoris shares a wealth of background history concerning the forcing of bulbs in her highly readable and valuable book, The Curious History of the Bulb Vase (Birmingham, England: Cortex Design, 2012).

See also Patricia Ferguson, “The Eighteenth-century Mania for Hyacinths,” The Magazine Antiques, vol. CLI, No. 6 (June 1997), pp. 844-851, for a historical overview of this subject with many illustrations of fashionable containers developed by ceramic manufactories of the 18th and 19th centuries for bulb forcing.

(iv) Ernst H. Krelage’s book, Drie Eeuwen Bloembollenexport (Three Centuries of Flower Bulb Export), published in 1946, mentions even earlier German and Swedish sources that illustrate the practice of forcing bulbs over water. See http://www.kennemerend.nl/history.html . Another helpful link on the general subject is https://oldhousegardens.com/HyacinthHistory .

(v) The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has an unusual pair of these Sèvres bulb pots from 1760 that once belonged to Queen Charlotte of England. Each of the four sides of the pots is decorated with a different ground color. See http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/bulb-pot-52673 .

(vi) In the Royal Collection there is also a Sèvres Pot-pourri Gondole, 1757-58 (RCIN 36099) which resembles a Venetian gondola and is “among the most ambitious vases produced at Sèvres; of particular complexity is the pierced onion-shaped floral cover, with four circular holes intended for hyacinth bulbs ….” (Catalogue entry from Royal Treasures, A Golden Jubilee Celebration, London 2002). See this link:

https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/36099/pot-pourri-gondole

(vii) https://www.meubliz.com/definition/bouquetiere/

(viii) Julie Berk, an avid hyacinth grower, has three websites: www.hyacinthvases.org.uk, www.gardenwithindoors.org.uk, and www.gardenwithoutdoors.org.uk .

(ix) Two more related square examples in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York can be seen online: they have the Accession Numbers: 17.190.1906 and 17.190.1909, and were formerly in the Gaston Le Breton collection of Rouen, France, until 1910; they were given by J. P. Morgan to the MMA in 1917. I attributed the decoration of both to Duvivier on p. 45, note 61 of In the Footsteps of Fidelle Duvivier (2016).

(x) As shown in C. Dauguet and D. Guilleme Brulon, Reconnaître les origines des Faïences françaises (Paris: Éditions Ch. Massin et cie, 1970), p. 51, no. 134.

(xi) In her book (note 3, pp. 26-31) Patricia Coccoris points out that Josiah Wedgwood was one of the first in England to seize upon the idea of manufacturing both “bough pots” (a lidded garden pot with holes to hold flowers or flowering boughs /branches) and “root pots” – for bulb forcing. He studied French examples made available to him and came up with a very creative line of shapes, using just about every possible body and surface treatment at his disposal (e. g. caneware, creamware, black basalt, jasperware and agateware), as the pictures at this Wedgwood Museum link show:

http://www.wedgwoodmuseum.org.uk/collections/search-the-collection/type/useful-warebulb-pot

(under TYPE click on “Useful ware – bulb pot” in the menu)