The museum’s porcelain collection features many examples decorated by Louis Victor Gerverot (s. Blogpost 1; photos 3, 6-8) and a Loosdrecht deep plate painted by Fidelle Duvivier (9a, b).

3 A Weesp porcelain tea cup, c. 1769, painted in colors with a bird of fantasy by Louis Victor Gerverot. H 3.1 cm (WP-14) Museum Weesp, the Netherlands. Photo by the author.

In particular, the museum has many examples associated with the Frenchman, Louis Victor Gerverot (1747-1829), who decorated porcelain tea and coffee services as well as tureens and platters with his colorful, original, and often quirky birds (3, 6-8). He went on to use this style in Germany (esp. at the Höchst manufactory), after Weesp closed its doors in 1771.(i) The only other reminder of the porcelain factory is a warehouse (4), still standing on the other side of the Oude Gracht canal, southwest of the present-day town hall. Here, manufacture and kiln firings took place at a safe distance from the city center, from 1759 to 1770.

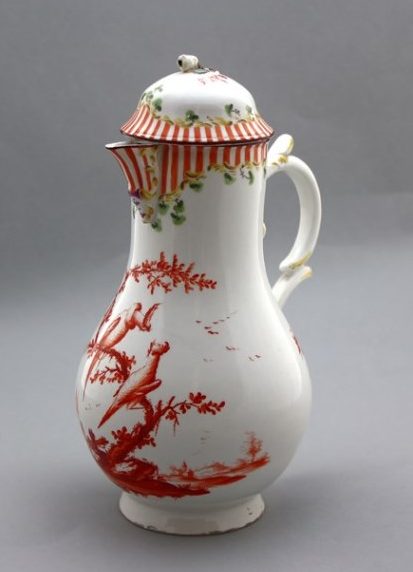

6 A Weesp porcelain teapot, c. 1769, decorated by Gerverot with birds of fantasy in colors, with a green bow pattern and gilding, and a scrolled rococo handle. H 9.5 cm. (WP-14A) (Cf. 3). Museum Weesp. Photo by the author.

Before porcelain production began, this building (originally a gin distillery) had been used for a couple of years by a group of men who had formed a partnership to make earthenware. Two years later one of them approached Count van Gronsveld-Diepenbroick-Impel (1715-1772) with the proposal of investing in a porcelain-making enterprise. Gronsveld was a nobleman who held several local titles and performed various official functions, having also served as envoy in Berlin at the court of Frederick the Great over a period of years until 1758. There he certainly would have laid eyes on collections of elegant Chinese and Meissen porcelain.(ii)

It was the period of the Seven Years’ War (1756-63), when many workers from Meissen were out of work and forced to look elsewhere for employment. It seems a number of them were engaged for a time at Weesp, and Gronsveld was hopeful that their know-how would make the young enterprise profitable. It’s well known that Meissen marked its porcelain with crossed swords in underglaze blue, so naturally the count would not have hesitated to mark his porcelain with a similar device derived from his own family coat-of-arms. This mark is shown on the plaque (5) mounted on the surviving warehouse. For a few years the porcelain did successfully find markets locally and abroad, but after the war, the sales were lagging well behind the growing production costs.

Louis Victor Gerverot, coming from Frankenthal in Germany, arrived in Weesp in late 1768 or early 1769 and probably stayed until just before the manufactory finally closed its doors in the spring of 1771. He had the good fortune to be hired as both a decorator and a coloeurmaker (color chemist). Being entrusted with the preparation of enamel colours was a well-paid task and it indicates that he had developed some competence in this area. The work must have appealed to him, even though these positions were short-lived due to the manufactory’s looming bankruptcy.

Gerverot’s painting on Weesp is strikingly colorful and his birds very lively and humorous-looking. At Weesp his style began to show a streak of independence from the rather formal, more serious Sèvres birds of fantasy still popular during this period. And he evidently was completely free to decorate services with these very unusual feathered creatures. There is no evidence that he was copying engraved sources or was compelled to conform to any “house style” of bird painting. These merry birds were all his own creations, and some of them appear on Höchst porcelain just a couple of years later, with just small changes to their plumes or other component parts.

His first type of bird decoration on Weesp was done in polychrome, and I refer to it as the “Green Bow Service” (3, 6). These bows and birds are found on two separate tea and coffee services (of which there are related pieces in various museums, including the Amsterdams Historisch Museum reserve collection, the Rijksmuseum, the National Museum and Gallery of Wales in Cardiff, and in private collections).

The second type of decoration (7) appears on twelve cups and thirteen matching saucers, all in the Museum Weesp. These are delicately painted with birds in puce, surrounded by a scalework border with gilded details. They truly belong to his best early work and delight the eye with their rhythmic movements.

The museum also owns a few pieces of a third service painted by Gerverot in a monochrome rouge de fer or iron-red color (8).(iii)

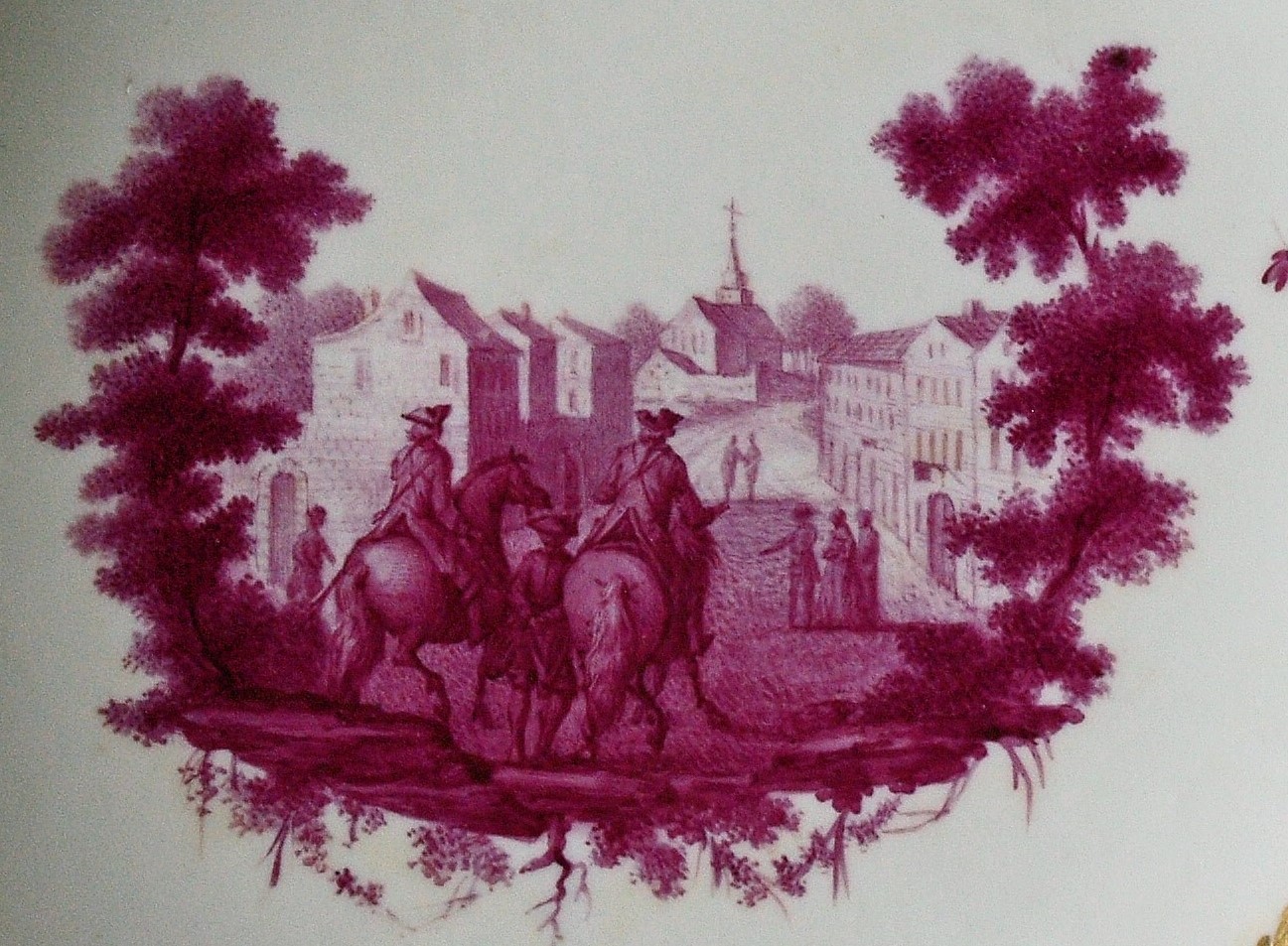

And finally, one more treasure in the Museum Weesp is this fine Loosdrecht dish decorated by Fidelle Duvivier with a military theme, which rarely occurs in his Dutch decoration. (Related pieces can be seen in the collections of Kasteel-Museum Sypesteyn, Loosdrecht, and in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam – see In the Footsteps of Fidelle Duvivier, pp. 61-62).(iv)

NOTES

(i) See the author’s articles, “Louis Victor Gerverot in a new light,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, (Brant Publications, Inc. New York), January 2004, pp. 192-199; and “Further Findings on the Life and Career of Louis Victor Gerverot,” American Ceramic Circle Journal, Vol. XIV, pp. 50-75 (April 2007), for more details on Gerverot’s life and career plus similar examples of his bird painting at Höchst, ca. 1771-1773. Two other articles were written in 2010 for the Dutch journal, Vormen uit Vuur, and the German periodical Keramos: “Louis Victor Gerverot – New Attributions,” Vormen uit Vuur, Nr. 201, 2010/4, pp. 8-15; and “War Louis Victor Gerverot in Fulda als Modelleur oder Maler tätig?” Keramos, 209, 2010, pp. 51-58. All of these articles can be read at the website www.academia.edu under ‘Charlotte Jacob-Hanson.’

(ii) W. M. Zappey, “Porselein en Zilvergeld in Weesp,” Hollandse Studien 12, (1982), pp. 167-196.

(iii) There is an associated Weesp milk jug to this service in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. See online collection (C.78-1956). Gerverot’s flower painting is represented in the Museum Weesp by two pieces featured in C. Jacob-Hanson, (2010), p. 10, figures 4 (coffee pot) and 5 (kraamterrine).

(iv) It is likely that Gerverot and Duvivier had met while the latter was employed at Loosdrecht, ca. 1780-84, and the former was living in Amsterdam, still financially connected to the manufactory. Later, in 1787, they briefly collaborated at John Turner’s Lane End factory in Staffordshire, England, most famously on the so-called “Gerverot Beaker.” See my article, “Louis Victor Gerverot – Before the Beaker,” The Northern Ceramic Society Newsletter, no. 188 (December 2017), pp. 18-28. Posted at www.academia.edu.

10 Map showing the location of Weesp. (For a map with the location of Loosdrecht,

see Blogpost #11 of December 3, 2017)

Very Nice story, Charlotte, Thank you for sharing With us.

Maybe you can point out Loosdrecht on the map as well. X Ernst

Dear Ernst, I could not make that addition to this map, but made a reference to Blogpost #11, where you can find a map with the location of Loosdrecht. Best wishes, Charlotte