1. Courtesy of Stichting Loosdrechts Porselein.

Diam. 25 cm

On the left side of this photo one sees a few parked cars in an open area. In 1998 a school on this property was torn down, allowing a team of local and professional archaeologists the

opportunity to systematically dig at the site of the 18th-century manufactory, which had been situated diagonally across the road from the Oude Kerk (or Old Church, seen at the left in the background).

While digging successfully down to the foundations of the main building and kilns, the team recorded a great variety of ceramic finds.(i) However, some of them had no immediate connection to the manufactory or to its workers since ceramic waste came from as far away as Amsterdam and some of it was as old as the fifteenth century. The Loosdrecht boatsmen had long been delivering peat (torf), cut and dried in blocks, to the city dwellers in the north, and made their return journeys with boatloads of waste, which was used to fill in the dug-out “veenland.” (Sensible refuse management!)

The area of water surrounding Oud-Loosdrecht (known as the Plassen in Dutch) increased in size as the peat-cutting continued over the centuries. It is no wonder that a great deal of the manufactory’s waste (broken saggars, misfired porcelain and other materials) was discarded in the water rather than buried on land. Even today, residents still continue to find sherds, wasters, kiln furniture and other valuable evidence in the shallow waters, with the finest specimens being catalogued and conserved by the Stichting Loosdrechts Porselein (SLOP), the local foundation of volunteers, and the Historical Society of Loosdrecht (HKL).

When looking at the beautiful specimens of Loosdrecht porcelain nowadays, we have little idea about what a risky and delicate business it was to fire these objects in the kilns of that age. The porcelain usually underwent up to four firings: first, the high-temperature biscuit and glost (glaze) firings, followed by the lower-temperature ones in a muffle kiln to fix the decora-tion or fire the gilding. In every case, the objects had to be placed in saggars that protected them from the extreme heat

2. Courtesy of Historische Kring Loosdrecht and Stichting Loosdrechts Porselein

and flying ash, and these saggars were stacked and positioned in the kiln by an experienced kiln master or his assistants. The kiln master was responsible for calculating the needed amount of fuel and the length of a firing. But despite his skills, something could always go wrong (2). It was not unusual for the “kiln losses” to amount to one-third or even one-half of the objects after an unlucky firing.

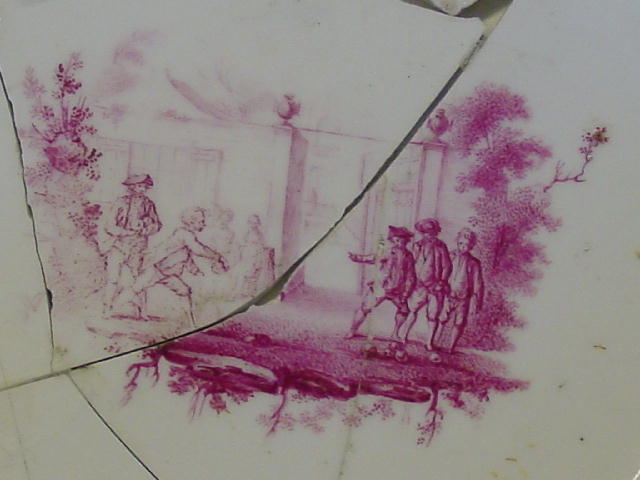

Fidelle Duvivier worked at Loosdrecht in the period c. 1780-84. His unmistakable style of decoration appears on a few discovered sherds. These examples of breakage – parts of a plate, a sugar bowl lid, and one other recovered object – are shown here:

1. – detail Courtesy of Stichting Loosdrechts Porselein

3. Courtesy of Stichting Loosdrechts Porselein.

Diam. 14 cm.

The sherds of the plate (a), showing some boys who appear to be playing a game of boules, were found in the water in 2001. The plate has been featured in two Vormen uit Vuur articles,(ii) and is associated with a large Loosdrecht service in Kasteel Duivenvoorde (see In the Footsteps of Fidelle Duvivier, pp. 62-63).

4. Courtesy of Stichting Loosdrechts Porselein.

7.3 x 3.4 cm.

On the lid of a sugar bowl (3) we see a couple walking through a park with a statue of a lion nearby. The sherd in (4) may have been part of a misfired bowl – or perhaps the sugar bowl belonging to the broken lid in (3). All three pieces were painted by Duvivier in puce camaieu, and it seems likely that (1) did not survive the final firing for the gilding, but cracked and broke; the same is true for (3) and one sees the gold was never burnished. The high rate of breakage was one reason the decorators may have customarily painted extra pieces for dinner and tea or coffee services.

Dear Charlotte – very exciting. And I am relishing the book. What a beautiful job you do! love