1a, 2a Both sides of a Chelsea-Derby teapot, ca. 1770, painted by Fidelle Duvivier, with winged putti on clouds, showing two with the emblems of literature and sculpture, plus a quiver of arrows (cf. 1b, 2b). Unmarked. H 8 cm. Author’s collection.

Luckily for me, the teapot pictured here did not sell last year at a porcelain auction in Heidelberg, Germany, and I was able to acquire it after the sale.(i) It was erroneously catalogued as Tournai porcelain, but is actually an English Chelsea-Derby teapot with a shape dating from the time Fidelle Duvivier was employed at the Derby factory (cf. 3). And what immediately caught my eye were those putti (cherubs) which I recognized as his work. In fact, they closely resemble those he painted later on Ansbach porcelain at the Lyncker decorating atelier in The Hague, ca. 1783 (cf. 4), as I described in a previous blogpost.(ii)

1b, 2b Details of the putti from both sides of the Chelsea-Derby teapot.

Sometime during 1768 or early 1769 Duvivier had come from the Sceaux manufactory in France to look for work in England. On October 31, 1769 he signed a contract with William Duesbury to work as a decorator at the Derby factory for four years, although we do not know whether he stayed at Derby the full four years.

3 A comparable Chelsea-Derby teapot of the same shape and age, showing what the missing lid would have looked like. Photo: W.W. Warner’s Antiques

4 Detail of two putti painted by Duvivier in polychrome on a later Ansbach bowl, painted in The Hague, ca. 1783. Private collection.

Although it has long been known that Fidelle Duvivier worked for Duesbury, there has never been any attempt in older Derby literature to attribute to him any early Derby decoration (often referred to as Chelsea-Derby).(iii) In fact, for decades most of the “cupid” decoration has regularly been attributed to another painter, Richard Askew, who worked for Duesbury only briefly in 1769/70, and again much later in 1794-95.(iv) As for Askew’s actual role in the Derby story, the long-standing biographical errors and speculations finally began to undergo some important rectification about ten years ago through the efforts of two gentlemen: the Derby expert and author, Sir Stephen Mitchell, as well as a Derby archivist, Andrew Ledger.(v) I have had the opportunity to correspond with both and expressed my interest in trying to positively identify Duvivier’s decoration on early Derby.

Since Duvivier did this type of popular Boucher-inspired decoration at nearly every manufactory where he worked, we can turn to a wealth of comparable examples when going about the work of identifying his hand on Derby porcelain. The two examples below illustrate a clear visual connection.(vi)

5 A Mennecy soft-paste porcelain jug with putti decoration in camaïeu rose by Duvivier, (c. 1766-68), in the collection of Hinton Ampner (National Trust). CMS_HIN0990. Hinton Ampner, Hampshire. © National Trust Images / Sophia Farley

6 A detail of a Derby cup and cover, c. 1770, decorated with a putto, trophies and doves by Duvivier. H 8.3 cm. Anchor mark (see 7) . The

V & A has more unattributed pieces of Duvivier’s Derby decoration. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London (inv. C.288 to B-1922).

For several years I have been collecting images of Duvivier’s Derby work with cherubs and flower painting of this period from collectors, museum collections, auction catalogues and other literature.(vii) We find his decorations on Derby tablewares, dessert services, tea and coffee services, as well as ornamental vases or vase garnitures. Two Derby examples were included in my Duvivier book and others have been shown in several past blogposts.(viii)

7 The conjoined gold anchor and D mark was introduced after William Duesbury acquired the Chelsea Factory Works in 1770, and used solely on porcelain made at the Derby factory. Photo: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

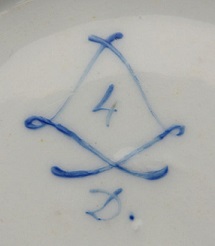

8 A mark that appears on a group of Derby wares that must have been decorated outside the Derby factory. Duvivier’s putti can be recognized on some of these wares. Photo: Stephen Mitchell

In his book The Marks on Chelsea-Derby … Stephen Mitchell discussed a group of Derby wares that bear “Sèvres-style” marks with the numbers 2, 4 or 6 painted in the center of the interlaced L’s (as shown in 8), and he concluded that these pieces must have been done outside the factory.(ix) Possibly up to three different painters were involved in this side-business, and one of them was Fidelle Duvivier. We do not know if Duesbury was aware that this was going on, or would have allowed painters under contract to do this kind of outside work. And we can only speculate about the meaning of the pseudo-Sèvres marks: perhaps they were used to promote the quality of the outside-decorated wares. The mark shown in (8) is definitely associated with Duvivier because it also appears on a Chinese cup and saucer he painted during this time.(x)

With all of this puzzling evidence, we return to the curious unmarked teapot shown at the start of this blogpost. The unanimous opinion of those I queried about the piece was that it also falls into the category of “outside-decorated” Derby porcelain. The gilded lattice decoration as well as the green band around the rim are not typical Derby decoration. But Duvivier lavished a good deal of attention on the delicate polychrome putto decoration, which he was responsible for introducing at Derby, after all.

NOTES

(i) From the Alexander Tafel collection auctioned at the Auktionshaus Metz in Heidelberg on May 18, 2019, lot 802.

(ii) See blogpost of February 27, 2018, “More Cherubs on Clouds, Painted in The Hague,” https://chjacob-hanson.com/more-cherubs-on-clouds-painted-in-the-hague/

(iii) It was referred to as Chelsea-Derby since William Duesbury, owner of the Derby factory, bought the Chelsea factory in February 1770 and operated both until 1784, when the Chelsea factory was closed.

(iv) The prolific researcher Major William H. Tapp wrote an article in 1934, in which he formulated his theories about the Derby painter, Richard Askew, falsely claiming that he was working at Derby for the entire period of 1770 to at least c. 1780. For this reason most auction houses still attribute most cupid decoration to him.

(v) In 2009 Derby expert Sir Stephen Mitchell wrote in his book, The Marks on Chelsea-Derby and Early Crossed Batons Useful Wares, 1770-c.1790. Chapter IX: A Sèvres-style mark, the “Dot Rose” painter and Fidelle Duvivier: outside decorators located in Derby c. 1768-1773?” (SGM Books, London, 2009, p. 36): “Although traditionally ‘cherubs on clouds’ decoration in camaieu rose is attributed to Richard Askew, there is now a strong case for attributing certainly some of that work to Fidelle Duvivier,” and he made several convincing attributions to him in this book. Andrew Ledger, an archivist at Derby, investigated the matter and published his findings in 2010. He discovered that Askew was only sporadically in Duesbury’s employ during 1769 until April 1771, but by April 1772 he was living in London and did not return to Derby to work there again until about 1794. So Askew could not have painted all of these “cherubs on clouds” over a period of 22 years. I will be explaining these findings in more detail in a forthcoming publication (see note vii).

(vi) For more details about the Mennecy jug (5) see blogpost of May 10, 2019, “A Mennecy Jug in a National Trust House,” https://chjacob-hanson.com/a-mennecy-jug-in-a-national-trust-house/

(vii) I am planning to create a small publication describing these collected images and comparing them to his earlier and later decorative work in France and Holland. I hope to include a CD of numerous examples that can be viewed by researchers using a laptop.

(viii) See In the Footsteps of Fidelle Duvivier, p. 65 (77, 78).

(ix) Mitchell (2009), op. cit., pp. 38-40.

(x) See Footsteps, p. 57 (63 a, b, c). The same maritime scene also appears on a faience plate Duvivier decorated at Sceaux. See Footsteps, p. 28 (39).

Ich freue mich, dass Du uns an Deinem Wissen der Geschichte über Duvivier teilhaben lässt. Danke für die schönen Bilder.