1 A detail of the neoclassical Loosdrecht vase at right, showing a draped putto or child holding a ribbon attached to a bat, painted in puce monochrome by Fidelle Duvivier,

c. 1780-1784. H 24.2 cm.

Photos: Woolley and Wallis, Salisbury, England (i)

Not long ago several pictures of this very unusual Loosdrecht vase (auctioned in England in 2014) were sent to me by its present owner. A rare and curious vase, indeed, for its painted decoration, done by Fidelle Duvivier. We see a draped putto or child holding up a ribbon from which a bat hangs with its wings extended. The vase is unmistakably neoclassical in style, but what is the bat meant to signify in this decoration?

I found an answer to this question in one dictionary of symbols: “In Italian Renaissance allegory [the bat] is an attribute of Night personified.”(ii) And since we can assume that this vase was one of a pair, its pendant would have had similar decoration but with an allegorical depiction of day or morning. I asked Constance Scholten, an art historian with a specialization in iconography, about this and she said the other vase would most likely have had a rooster (cock) as the representation of day in its decoration.(iii)

Prior to this piece, the only other Loosdrecht vases with decoration by Duvivier that I had seen was a pair in the Rijksmuseum reserve collection (3a), one of which was featured in my Duvivier book (pp. 67-68, see below) and had been included in the 1988 Rijksmuseum exhibition and catalogue, Loosdrechts Porselein, 1774-1784.(iv)

3a One of a pair of Loosdrecht porcelain vases and covers with putti decoration by Duvivier, the handles as ram’s heads, c. 1783. H 25 cm. ©Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RBK 14343 A).

3b The cover of the vase shows familiar “trophy” details symbolizing music and literature, along with a quiver of arrows. Photo by the author.

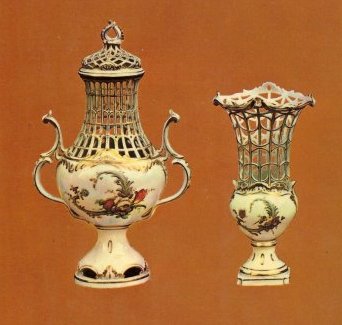

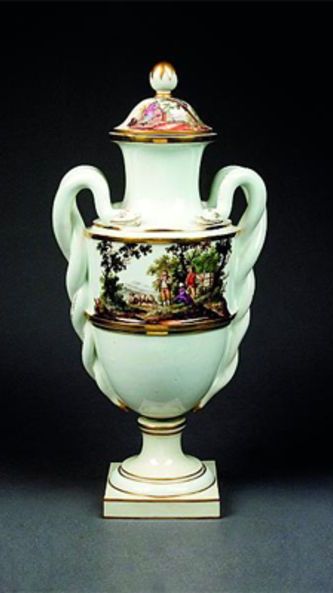

We find ample evidence that decorative vases were produced at Loosdrecht, which confirms several things. It demonstrates that Rev. de Mol intended to appeal to the tastes of the affluent classes and strengthen the manufactory’s competitive position. And it also shows an awareness that the ornamental vase had become the most fashionable interior design accessory at this period of the 18th century. As was commonly being done elsewhere, Loosdrecht copied vase shapes made by a number of other manufactories, such as Tournai (5), Fürstenberg, and Sèvres. But the reticulated, Tournai-inspired vases in (4) with their rococo openwork shapes and handles would have been time-consuming to make, a challenge to fire in the kiln, and very expensive as a result.(v)

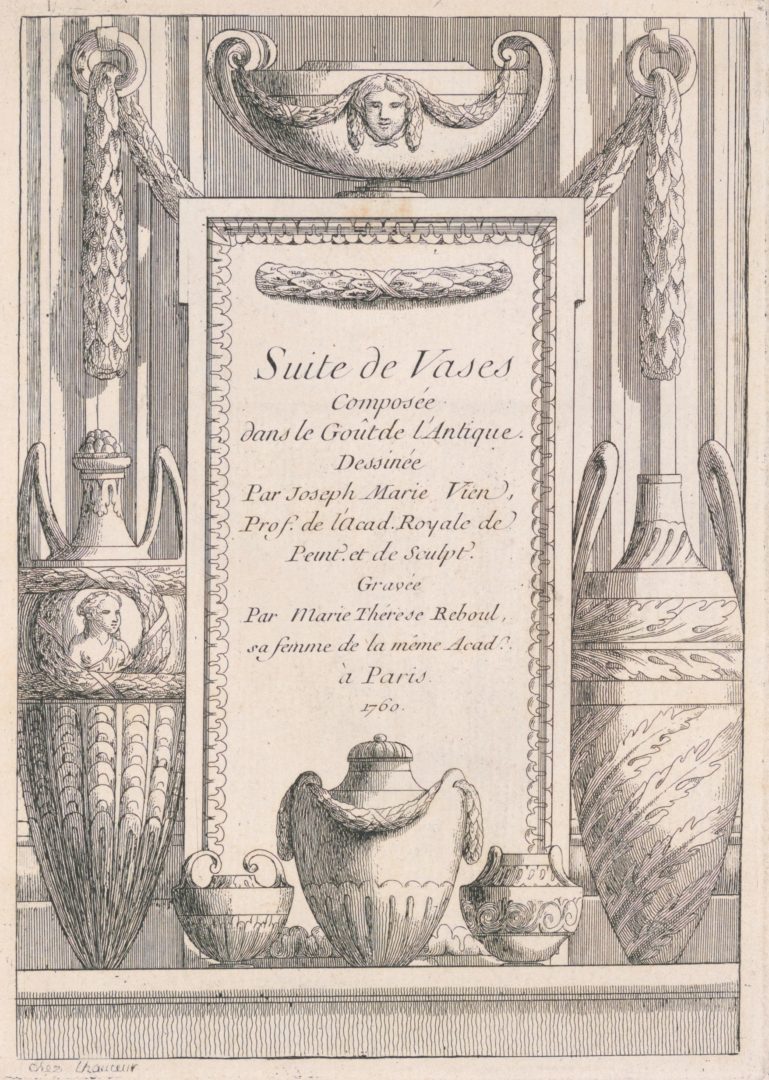

Actually, by this time, there was a greater market for a vase style that reflected the widespread European interest in classical antiquity. This new style dans le goût de l’antique (“in the antique style”) had already begun to manifest itself in painting, sculpture, furniture, and interior design.(vi) There were several contributing factors to the spread of this fashion that would come to be known as Neoclassicism: the phenomenon of the Grand Tour, the archaeological wonders excavated at Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748), and the genius of the partners, Wedgwood & Bentley, in Staffordshire.

By 1750 the Grand Tour had become an established tradition for wealthy European nobility and/or their heirs. They traveled through Europe for the purpose of completing their education and refining their taste by being exposed to history, culture, and art (having the opportunity to collect the latter), while contemplating the remnants and legacy of ancient civilizations. Greece and Rome were revered as the pinnacles of civilized societies, having furnished the roots of Western civilization.

Wedgwood did not hesitate to seize upon this fascination with antiquities and the Grand Tourist market. Bentley had traveled widely on the Continent and could supply his partner with published Books of Vases containing engraved source material (6).(vii) It should be mentioned that some of these prints and engravings of the 17th and 18th centuries were plainly fanciful inventions rather than true copies of ancient vessels, but they provided elements that could be borrowed, altered, and adapted. Wedgwood was one of the first English potters to make vases of earthenware, and was also the first potter to make ceramics for interior decoration. In May 1769 he proudly wrote of the crowds of ladies and gentlemen storming his London showroom, reporting that “Vases was all the cry.” By 1772 he had more than one hundred vase shapes to which he could add different handles or applied ornaments, with a variety of ceramic bodies and surface treatments to choose from (7). (A catalogue was published in 1773 to advertise, and to facilitate orders and sales at home and abroad).

7 A pair of Wedgwood porphyry vases and covers, circa 1775, of urn shape with fluted borders, the finely modeled scrolled handles and applied swags picked out in gold, the creamware bodies mottled in green and black to simulate Serpentine. H 33.8cm. Photo: Bonhams

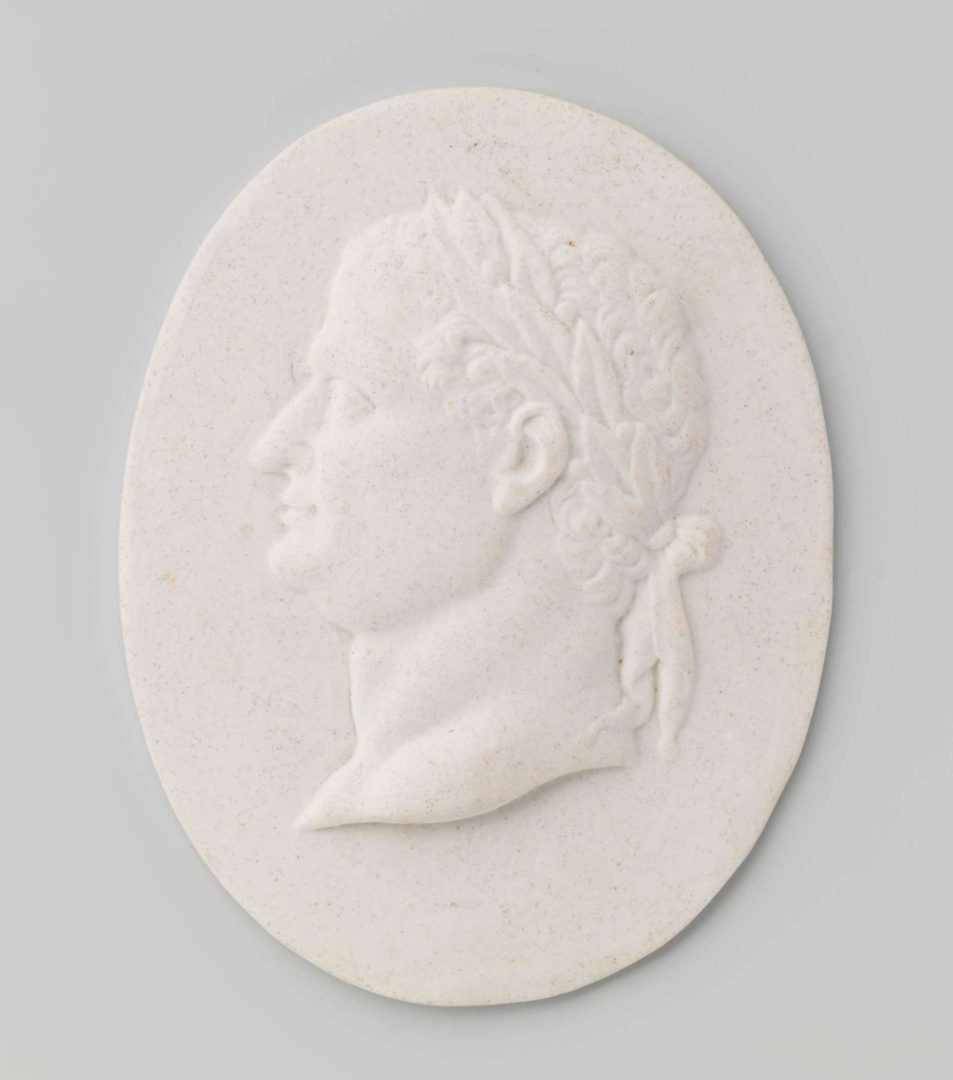

Although De Mol did not make direct copies of any of Wedgwood’s vases, the fact that he did attempt to make a set of biscuit porcelain portrait medallions of famous Roman emperors (12), very much in the style of Wedgwood’s intaglios, indicates that he may have had customers interested in the kind of popular Grand Tour souvenirs Wedgwood was making (see Loosdrechts Porselein, p. 300, no. 270; now in the Rijksmuseum collection).

But stylistically, the predominant French Louis XVI-style appears to have had the strongest influence on Loosdrecht’s vase production. The Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory had created many new ceramic interpretations of ancient vessels by 1780. Again we notice that most of their earliest vases of the 1760s “bear little resemblance to vase designs actually used in the ancient world, [but] evoke antiquity in a more imaginative way. Many examples adapt motifs from classical architecture and ornament or draw on Renaissance interpretations of ancient vessels. With the goût grec vase, [as they called it], designers helped to establish the ornamental canon for neoclassical decorative arts, which favored motifs such as heavy laurel garlands, Greek meanders, geometric forms, rams’ heads, and satyr masks, all arranged in strict symmetry.” (Quoted from link, note vi). (These motifs are shown in examples 2, 3a, 8, 10 and 11).

One vase in the Kasteel Sypesteyn collection illustrates a close connection to Sèvres:

< “This vase is rare and an exact copy of a Sèvres vase (r.). The original was made by Josse François Joseph Le Riche, Head of the Sculpture Department of Sèvres, (1757-1769; 1775-1801). The Vase aux serpents by Le Riche was produced in 1781. Therefore the maker in Loosdrecht must have seen the example from Sèvres. The method of painting and the colour scheme are, however, completely different here. … Loosdrecht must have been a close follower of fashion.”(viii)

H 27.9 cm. Kasteel-Museum Sypesteyn, Loosdrecht, (inv. 8943).

11 A neoclassical Loosdrecht vase (one of a pair), c. 1780,

H 24.7 cm. Kasteel-Museum Sypesteyn, Loosdrecht (inv. 8914 a,b) (ix)

NOTES

(i) Auctioned on 25 Feb. 2014, lot 353, Woolley and Wallis, Salisbury, England: “A Loosdrecht Neoclassical vase Middle Period (c. 1778-82), painted in puce with a vignette of a child draped in cloth and holding a bat, within laurel garlands, the sides applied with further garlands, raised on a square foot, incised M:O.L. mark, H 24.2 cm.”

(ii) James Hall, Illustrated Dictionary Of Symbols In Eastern And Western Art (Routledge, 2018), p. 10.

(iii) My thanks to Constance Scholten, formerly conservator for iconography at the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie (RKD) in The Hague, and author of Haags Porselein, 1776-1790. Een ‘Hollands’ product volgens de internationale mode (Waanders, Zwolle, 2000). See also Blogpost #13, “More Cherubs on Clouds, painted in The Hague” (February 27, 2018).

(iv) Wilhelmus M. Zappey et al., Loosdrechts Porselein 1774-1784, ed. Abraham L. den Blaauwen (Zwolle, Netherlands: Waanders, 1988), p. 235. Color images can be found in the Rijksmuseum’s online collection.

(v) Ibid., p. 230, no. 164. Another 5-piece set is shown in Ank Trumpie, ed., Pretty Dutch. 18de-eeuws Hollands porselein. 18th-century Dutch Porcelain (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2007), p. 83 (Amsterdams Historisch Museum, KA 8117). The Rijksmuseum has another set with both Loosdrecht and Amstel marks, indicating that such garnitures or replacements continued to be made at Amstel after 1784. The Tournai garniture in (5) was featured in Claire Dumortier and Patrick Habets, Porcelaine de Tournai. Scènes galantes et décors historiés (2015), p. 99. My thanks to them both for the loan of this image.

(vi) See William Rieder, Heather Jane Mccormick, Hans Ottomeyer, Vasemania. Neoclassical Form and Ornament in Europe: Selections from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (2004), with helpful descriptions given at the following link: https://www.bgc.bard.edu/gallery/exhibitions/41/vasemania-neoclassical-form-and-ornament

For another informative link on vase garnitures see

http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/article/garnitures .

(vii) Wedgwood adapted several models from Stella’s Book of Vases, and later from Sir William Hamilton’s famous published collection of antiquities. See Hilary Young, ed. The Genius of Wedgwood, (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1995), pp. 102-117. The website of the Wedgwood Museum also offers a wealth of examples and background, e.g. http://www.wedgwoodmuseum.org.uk/learning/discovery_packs/pack/classical/chapter/neo-classicism-in-the-18th-century

(viii) Tamara Préaud’s comments in Pretty Dutch (2007), pp. 69-70. The pair of Sèvres vases to which the example at right (9) belongs was made for Madame Adélaïde, the daughter of Louis XV, in 1786.

See also

https://www.amisdeversailles.com/objet_detail.php?id_objet=126 .

(ix) Illustrated in Isabella von Marschall, “Klassizismus – Edele Einfalt, stille Grösse” in Von den Ursprüngen des europäischen Porzellans bis zum Art Déco (Wilhelm Siemen, Deutsches Pozellanmuseum, 2010), Band 104/1, p.153. The decorations on this pair of vases were based on illustrations of wall paintings uncovered in Herculaneum and published in Le Antichita’ Di Ercolano esposte. See http://www.accademiaercolanese.it/le-antichita-di-ercolano-esposte.html .

Another stunner. Fun for me because of the DuVivier angle but also because I think vases have been much neglected compared to other aspects of china. Thank you! Field