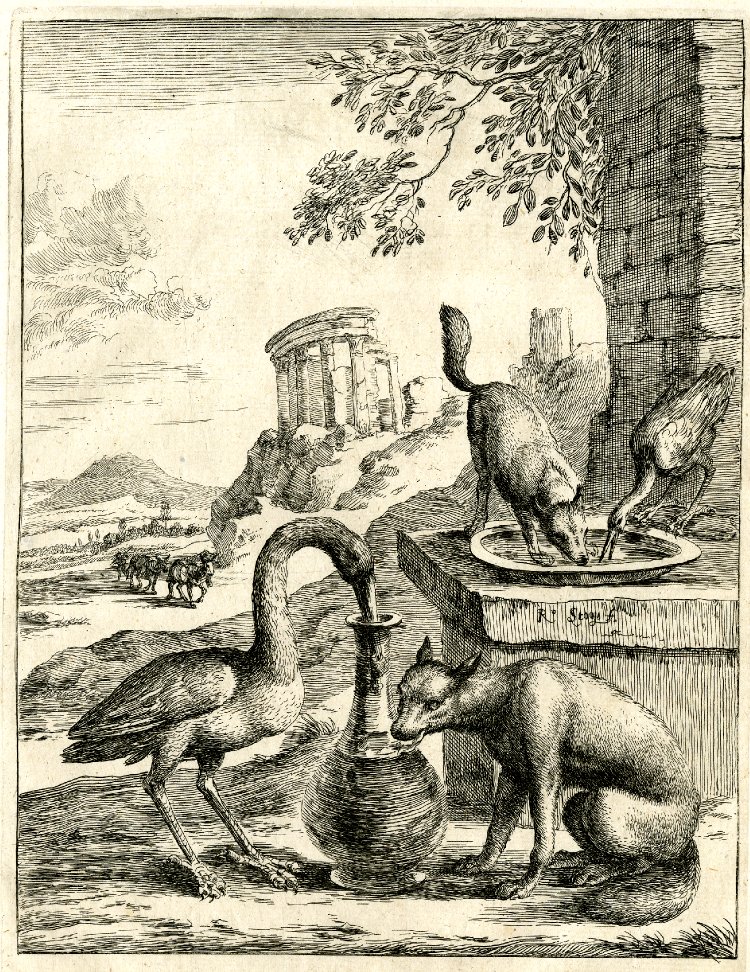

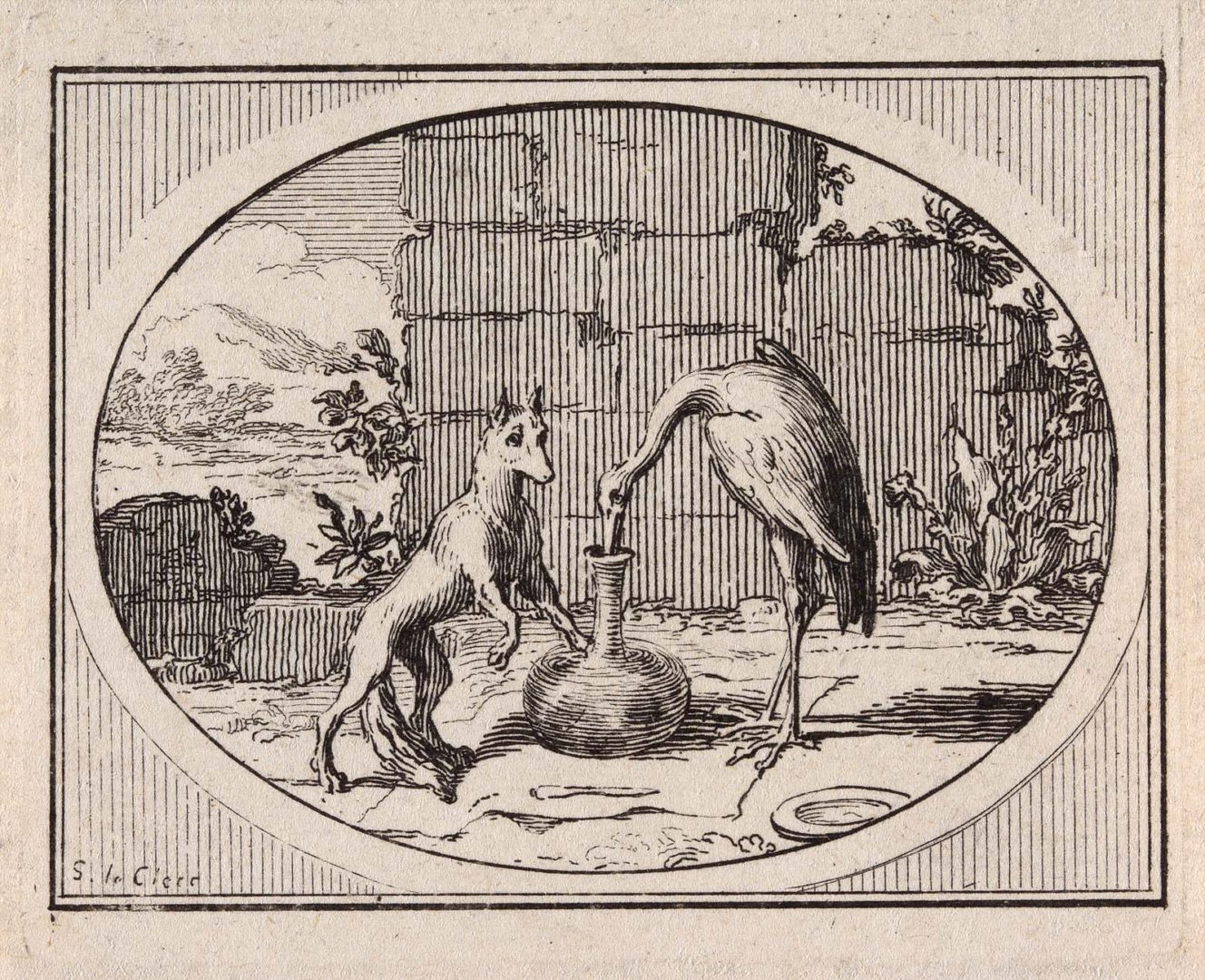

4 “The Fox and the Stork,” one of a set of twenty-two small oval engraved prints published in 1683 by Sébastien Le Clerc, royal printmaker to French King Louis XIV. © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (Museum purchase with funds donated by Ruth V.S. Lauer in memory of Julia Wheaton Saines)

The Victoria and Albert Museum has a tile made in Liverpool (probably by Sadler and Green), ca. 1770-ca. 1780, with this motif printed on it in black and in reverse (inv. 414:836/1-1885).

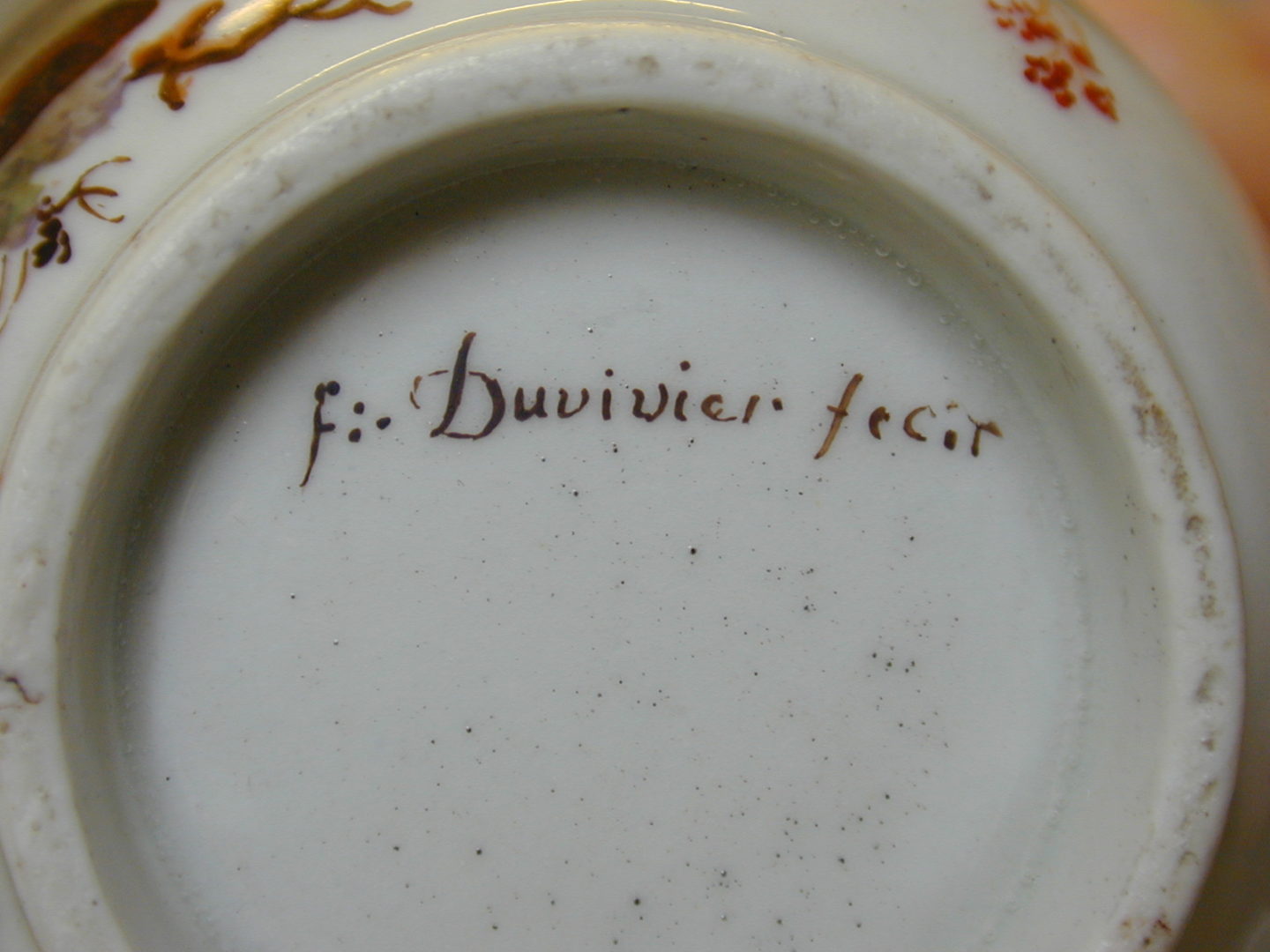

The signature. The fact that Fidelle Duvivier was allowed to sign this cup and the other New Hall pieces could indicate that they were all commissioned works, done outside the factory. It may imply that Duvivier was employed and paid as an outside decorator at New Hall during the years 1785 to 1790 (and later), since he was apparently allowed to work for other nearby factories and have two days free to teach drawing to children.

His signature on the New Hall mug in the Victoria and Albert Museum (6) closely resembles the one seen on the base of the fable cup (2); the vertical line extending upward from the capital D is conspicuous. But what do the three dots after the F signify? Several authors have stated that it suggests Duvivier was a freemason, having joined a lodge in Tournai very early in his life; however, these masonic connections have not been confirmed.

Attribution history. In English ceramic literature this cup went through a few faulty attributions before being identified as New Hall. In 1941 the earliest Duvivier researcher Major William H. Tapp deemed it a Worcester example; in 1951 Franklin A Barrett considered it to be either Caughley or early Coalport. But by 1978 David Holgate had correctly identified it as New Hall.(iv)

NOTES

(i) There is a twice-signed cylindrical New Hall mug in the Victoria and Albert Museum (C. 128.1977), one signature shown here (6); other pictures are shown online at their website. A second New Hall example is illustrated in In the Footsteps of Fidelle Duvivier (5 on p. 6) and presently on loan to the Potteries Museum, Stoke-on-Trent. A third signed piece is the porcelain “Gerverot Beaker,” made at the John Turner factory, dated 1787, and now in the British Museum, London (inv. 2010,8013.1). The fourth signed piece is a Worcester teapot, dated 1772, in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (see p. 56, no. 62a, b in Footsteps).

(ii) V. S. Vernon Jones, Aesop’s Fables. Facsimile of the 1912 edition (Wordsworth Classics, 1994), available online at www.gutenberg.org.

(iii) David Holgate, “Fidelle Duvivier Paints New Hall,” ECC Transactions, Vol. 11, pt. 1, (1981), p. 19.

(iv) Geoffrey Godden discussed these attributions in his New Hall Porcelains (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2004), p. 161, 181.